Die gefährlichen Verlockungen des Staatsfernsehens

Wer, wie ich selber, einmal als Reporter im Schweizer Fernsehen gearbeitet hat, weiß, wie der staatliche Sender mit Menschen umgeht, die er weltanschaulich nicht mag. Wer das nicht weiß, muss die Erfahrung wohl einmal machen. Davon handelt diese Geschichte.

Prisca, Roman und Christian gehören der «Graswurzle» an, einer freiheitlich gesinnten Gruppierung aus der Coronazeit. Außerdem zeichnen die drei für die Monatszeitschrift Die Freien verantwortlich. Eines Tages erhalten sie die Anfrage eines Fernsehsenders. Sie werden mit freundlichen Worten gefragt, ob sie Teil einer Reportage sein möchten, die sich mit den durch Corona entstandenen unvereinbaren Fronten befasst.

Der Fernsehsender ist aber kein Privatsender. Es ist DER Sender der Schweiz. Donat Hofer ist Filmemacher bei SRF. Er wolle darüber sprechen, erklärt er sein Filmprojekt, wie man sich noch verständigen kann, wenn «die Vorstellung davon, was richtig und falsch ist, so stark auseinandergeht».

Donat setzt, wie er schreibt, «auf gegenseitiges Zuhören und Verstehen wollen», und er verspricht eine «Begegnung auf Augenhöhe». Das wäre eigentlich selbstverständlich. Warum muss der Filmemacher es so betonen?

Roman, der das Mail liest, spürt vielleicht mehr, als er wissen kann. In einem ersten Impuls will er die Anfrage löschen. Aber Prisca, Christian und er müssen gemeinsam beschließen, wie sie antworten sollen. Während sie noch am Besprechen sind, ruft der Fernsehmann Prisca an. Während fast einer Stunde versucht er ihr zu vermitteln, dass es nicht seine Absicht sei, sie in einem schlechten Licht darzustellen. Seine Hoffnung sei es, erklärt er, einen Dialog zustandezubringen, eine Brücke zwischen den Fronten zu bauen.

Gleich zu Beginn trägt er Prisca das Du an – «weil wir doch letztlich das Gleiche wollen: Uns gegenseitig besser verstehen, oder nicht?» Prisca schenkt ihm Vertrauen, und sie beschließen, beim Filmprojekt mitzumachen. Die Gelegenheit, dem Mainstreampublikum ihre Sichtweise näherzubringen, wollen sie nicht ungenutzt lassen.

Schon um 8 Uhr morgens will der Filmemacher bei ihnen im Urnerland sein, wo die «Graswurzle»-Bewegung ihren Sitz und ihre Adresse hat. Doch der SRF-Mann erscheint erst mit fast einer Stunde Verspätung. Die Wartenden erleben bereits vor der Ankunft des Journalisten, dass er vor ihnen keinen großen Respekt hat. Als müssten sie dankbar und froh sein, dass er zu ihnen kommt.

Roman – so wird er dies später erzählen – findet das Verhalten des Fernsehmannes vom ersten Moment an grenzüberschreitend. Der Typ macht auf Kumpel, der er nicht ist, und bewegt sich in der Redaktion von Die Freien, als hätte er dazu jedes Recht. Er filmt penetrant und fast pausenlos und ist es offensichtlich gewohnt, dass die Gefilmten alles brav mitmachen.

Was die drei Graswurzle-Menschen zu sagen haben, will er nicht wirklich wissen. Sobald sie auf Corona zu sprechen kommen, weicht er aus, und wenn sie wichtige kritische Stimmen zitieren, gibt er bloß zu erkennen, dass er all diese Namen noch nie gehört hat. Nicht einmal die Rolle eines Bill Gates während der Pandemie ist ihm bekannt.

Die drei Medienschaffenden gewinnen den Eindruck eines unprofessionellen und unvorbereiteten Journalisten, der überhaupt gar nicht zuhören will, sondern lieber streitet, und Prisca, Roman und Christian herablassend vorwirft, sie seien bei Corona «auf dem falschen Weg abgebogen».

SRF-Journalist Donat Hofer nach seinem Besuch bei den «Verschwörungstheoretikern», die keine sind (Bild: Screenshot «Im Sog der Verschwörungstheorien», SRF)

Als er am Ende des Tages mit mehreren Stunden Filmmaterial wieder abzieht, geht es den Zurückgebliebenen schlecht. Sie fühlen sich manipuliert und missbraucht, und sie teilen dem Fernsehmann mit, dass sie ihr Einverständnis zurückziehen.

Das erträgt dieser Donat Hofer nun gar nicht. Er telefoniert mit Prisca und versucht sie mit einem geradezu hektischen Eifer zu überzeugen, ihm eine zweite Chance zu geben. Es tue ihm leid, argumentiert er, wenn der Eindruck entstanden sei, er wolle sie in die Pfanne hauen. Das sei nicht seine Absicht. «Ich möchte euch wirklich verstehen», beteuert er wortreich. «Ich verspreche euch eine faire Darstellung, da machen wir etwas Schönes draus, das wird eine gute Sache!»

Wiederum bekommt Prisca den Eindruck, er meine seine Beteuerung ernst, und sie vereinbart mit ihm einen zweiten Drehtag. Diesmal trifft Donat pünktlich ein, und er scheint sich tatsächlich vorgenommen zu haben, auf seine Gastgeber zuzugehen. Er hat sich von ihnen auch bereitwillig eine umfangreiche Dokumentation zusenden lassen, die einen alternativen Blick auf die Corona-Zeit wirft.

Als sie ihn darauf ansprechen, gibt er freimütig zu, dass er noch nicht dazukam, darin zu lesen. Doch die drei geben sich damit zufrieden. Neues Misstrauen hegen sie nicht, denn dieser zweite Drehtag verläuft tatsächlich aufbauender als der erste. Donat Hofer hört ihnen zu und vermittelt ihnen den Eindruck, er nehme sie ernst. Die Stimmung ist so gelöst, dass Prisca und Roman den SRF-Mann bei sich zuhause zum Mittagessen einladen. Man versteht sich prächtig, ein gutes Gespräch entsteht und bei Jean Zieglers Kapitalismuskritik findet man sogar gemeinsame Nenner. Jedenfalls kommen Prisca und Roman zusammen mit Christian danach zum Schluss, ihre Zustimmung nicht mehr zurückzuziehen. Sie glauben, dass sie viele wichtige Aussagen einbringen konnten, die durch den Fernsehfilm eine breite Öffentlichkeit erreichen.

Das von ihnen Gesagte, das ist ihnen klar, wird nicht ungekürzt ausgestrahlt werden. Aber zumindest kommt ihre Stimme im Mainstream zu Wort. Sie glauben auch den Versicherungen des SRF-Mannes, dass er ihnen soweit als möglich gerecht werden wolle. Sie begnügen sich mit dem Zugeständnis des Fernsehens, ihre im Film gemachten Äußerungen in schriftlicher Form zu erhalten. Den ganzen Film bekommen sie vor der Ausstrahlung nicht zu sehen. Offenbar ist das beim Fernsehen so üblich.

Als sie ihre Aussagen schwarz auf weiß lesen, erschrecken sie. Das meiste, was sie an alternativen Fakten über Corona und andere Themen dargelegt haben, wurde vom Filmemacher gestrichen. Von den fast achtstündigen Filmaufnahmen hat er hauptsächlich jene Szenen verwendet, wo er mit Prisca, Roman und Christian pauschal über Journalismus und Wissenschaft streitet – und darüber, dass man sich zwar menschlich sympathisch sein mag, in der Sache aber keine Verständigung findet.

Donat Hofer macht ihnen klar, dass er die verwendeten Filmaufnahmen nicht mehr ergänzen oder erweitern wird. Müssen sie das zusammengestauchte Endresultat also schlucken? Noch immer im Glauben, er wolle ihnen nicht wirklich schaden, fragen sie ihn, was für Möglichkeiten ihnen noch bleiben. Doch der vorher so kollegial auftretende SRF-Journalist ist auf einmal nicht mehr gesprächig. Er gibt ihnen keine Antwort.

Trotzdem entscheiden sich Prisca, Roman und Christian, nichts mehr zu unternehmen. Auch wenn der Filmemacher das meiste weggekürzt hat – zu ihren noch verbliebenen Aussagen können sie stehen. Wie er ihre Worte einordnen, wie er sie kommentieren wird, wissen sie allerdings nicht.

Prisca und Christian beim Betrachten der neuen Nummer von Die Freien (Bild: Screenshot «Im Sog der Verschwörungstheorien», SRF)

Dann meldet sich Donat wieder und kündigt ihnen die Ausstrahlung des Filmberichts an. Er habe versucht, das Ganze so ausgewogen wie möglich zu machen, aber – so schreibt er weiter – «ihr werdet vermutlich keine grosse Freude haben daran».

Als sich dann Prisca, Roman und Christian den Filmbericht anschauen, ist ihre Betroffenheit groß. Donat hat ihnen verschwiegen, dass der Film zum Auftakt einer SRF-Themenwoche gesendet wird, die sich mit der Fragestellung «Fakt oder Fake?» befasst. Dies allein lässt schon Schlimmes befürchten. Was die drei aber noch mehr empört, ist der nun gewählte Titel der Reportage: «Im Sog der Verschwörungstheorien – Wenn Misstrauen das Weltbild prägt».

Das Endprodukt selbst bestätigt die ungute Vorahnung. Aus dem Versprechen des SRF-Mannes, mit der Sendung eine Brücke bauen zu wollen, wurde ein Beitrag, der Prisca, Roman und Christian als politisch naive und zugleich unberechenbare Medienschaffende darstellt, die in den «Sog» von Verschwörungstheorien geraten sind.

Die drei sehen sich auch missbraucht für die SRF-Propaganda gegen die Halbierungsinitiative, die dem Staatsfernsehen einen Teil der Zwangsgebühren wegnehmen will. Nicht zufällig wurde die Themenwoche im Vorfeld der Abstimmung ausgestrahlt. Zusammen mit Gleichgesinnten in den anderen Teilen des Filmberichts sollen die drei als warnende Beispiele dienen für Zeitgenossen, die an «Fake News» statt an die Wahrheit glauben. Und die Wahrheit kennt nur das staatliche Fernsehen.

Die drei müssen erkennen, dass ihr vermeintlich netter Kollege von nebenan sie schamlos hinters Licht geführt hat. Derselbe Typ, der vor allem Prisca dafür kritisierte, dass ihre ganze Haltung geprägt sei von Misstrauen, hat das Vertrauen, das sie ihm schenkte, benutzt, um den Film zu drehen, den seine Vorgesetzten von ihm erwarteten.

Dass auch er selber hinter seinem Filmbericht steht, zeigen nicht nur die von ihm gesprochenen Kommentare, sondern auch seine Fragen im Gespräch mit einem «Experten» einige Tage später. Der Herr heißt Dirk Bayer. Er soll die Äusserungen der Protagonisten im Film als Kriminologe beurteilen.

Donat Hofer fragt den Kriminologen Dirk Bayer, ab wann Verschwörungstheoretiker «gefährlich» sind (Bild: Screenshot «Im Sog der Verschwörungstheorien», SRF)

Allein schon die Wahl eines Dozenten für Kriminalistik verdeutlicht, in welch trübes Licht Menschen gerückt werden sollen, die dem Mainstream verloren gingen. Und offenbar ist Dirk Bayer genau der richtige Mann.

Zunächst unterstellt er Prisca und ihren Mitstreitern wörtlich, mit ihrer Systemkritik die Demokratie zu «zersetzen». Als ihn Donat Hofer dann fragt, ab wann die Kritik «gefährlich» werde, erwidert der deutsche Professor, ohne mit der Wimper zu zucken: Eine Kritikerin wie Prisca könne zwar nicht direkt als gefährlich bezeichnet werden. Aber in ihrem Schlepptau könnten sich Radikalere mobilisieren, die das System dann tatsächlich angreifen. Mit anderen Worten: Prisca, die Brandstifterin.

Donat Hofer widerspricht dem akademischen Scharfmacher nicht. In keiner Weise glaubt er, Prisca beschützen zu müssen. Obwohl er in ihrer Küche saß, ihren Kaffee trank und ihre kostbare Zeit stahl, lässt er den Satz, sie «zersetze» die Demokratie, einfach stehen. Spätestens jetzt gibt der SRF-Journalist zu erkennen, dass er von Anfang an verliebt in sein Selbstbildnis war: in das täuschend jungenhafte Bild eines engagiert fragenden Hans Guck-in-die-Luft mit offenem Herzen, der in Wirklichkeit ganz genau weiß, was er von Mitmenschen hält, die seine materialistische Weltsicht nicht teilen.

Obwohl sich Prisca, Roman und Christian von ihm hereingelegt fühlen, verteidigen sie ihre Zustimmung zur SRF-Reportage. Sie haben sich für ein Ja entschieden, weil das staatliche Fernsehen «ausgewogen» und «objektiv» zu berichten hat. Deshalb haben auch sie den berechtigten Anspruch, ihre Haltung im Fernsehen erklären zu können. Das SRF ist auch ihr Fernsehen. Weil auch sie die Zwangsgebühren bezahlen müssen.

Dass sie richtig entschieden haben, zeigt ihnen auch die große Verbreitung des Filmberichts. Allein auf YouTube haben ihn über 18.000 Menschen gesehen; über 2.000 haben ihn kommentiert, nicht zu reden von all den Tausenden, die sich ihn im Fernsehen angeschaut haben.

Unter all diesen Menschen waren natürlich viele, die so denken wie Prisca, Roman und Christian. Sie haben sich durch das Gehörte in ihrer eigenen Haltung bestätigt gefunden. Und geärgert haben auch sie sich über das staatliche Fernsehen, das kritische Zeitgenossen ein weiteres Mal zu «Verschwörungstheoretikern» macht. Manche haben darauf sofort ein Abonnement für Die Freien gelöst. Mit Genugtuung stellt die Redaktion fest, dass zurzeit täglich neue Abonnenten hinzukommen.

Doch vor allem haben Menschen den Film gesehen, die man dem Mainstreampublikum zurechnen darf. Einen anderen Grund für die große Zuschauerzahl kann es nicht geben. Die Sympathie dieser Mehrheit, so lässt sich fast mit Sicherheit sagen, gehört aber nicht den kritischen Protagonisten, sondern dem Filmemacher. Viele Zuschauerkommentare sagen dasselbe wie er. Sie spotten über die Graswurzle-Menschen und werden am 8. März mit derselben Überzeugung wie vorher gegen die Initiative stimmen, die ihnen ihr Fernsehen kaputtmachen will.

Bestimmt wird es auch Menschen im Mainstreampublikum geben, die der Film zu Gedanken anregt. Zu kritischen Gedanken. Aber das werden nicht viele sein. Denn der Film ist kein Film, der in der Mitte zwischen den Fronten steht. Er gibt dem unvoreingenommenen Zuschauer nicht die Möglichkeit, sich ein eigenes Urteil zu bilden. Der Film ist ein SRF-Film, und für die Verantwortlichen war von Anfang an klar, dass ein Propagandafilm daraus werden muss. Ihr Vorgehen war darauf angelegt, dass Prisca, Roman und Christian auf keinen Fall gut wegkommen dürfen.

Und so geschah es. Sie kamen schlecht weg. Zwar durften sie ein paar wichtige, gute Sätze sagen. Aber diese paar guten Sätze waren umzingelt von Propaganda. Auch der Druck, unter dem die Drei standen, das ihnen Wesentliche sagen zu können, war spürbar. Sie sind die «Freien», doch sie fühlten sich unfrei, ausgeliefert dem SRF-Mann, der sie zu Aussagen hinriss, die sie genauer hätten erklären wollen. Aber das Wesentliche, wie gesagt, interessierte ihn gar nicht. Und er war der Regisseur. Er bestimmte den Lauf des Gesprächs, das im Grunde ein Schlagabtausch ohne echte Substanz war. Ein psychologisches Katz-und-Maus-Spiel. Per Du.

Schuld daran, dass es so herauskam, waren sicher nicht Prisca, Roman und Christian. Aber sie haben mitgemacht. Sie stellten sich zur Verfügung.

***

Ich habe selber einst beim Schweizer Fernsehen gearbeitet. Als Reporter der «Tagesschau». Und ich habe mich wiedererkannt. In Donat. Denn so war es doch: Wenn du als SRF-Mensch irgendwo aufkreuzest, dann bist du wer. Dann bist du einer vom Fernsehen. Von DEM Fernsehen. Das gibt dir von vornherein ein Prickeln von Macht. Besonders bei politischen Themen. Dann hast du schon bei der Ankunft am Drehort eine klare Vorstellung davon, was du ins Studio zurückbringen willst. Welche Aussage du vermutlich verwenden und welche du löschen wirst. Du gibst dich offen und lernbereit, obwohl dein Urteil vom ersten Moment an feststeht.

Sind es politische Gegner, mit denen du sprichst, dann weißt du zwar, dass sie gegen dich sind. Aber gleichzeitig bist du einer vom Fernsehen, und du spürst, sie wollen im Fernsehen kommen, weil es DAS Fernsehen ist, und weil sie die Chance, das ganz große Publikum zu erreichen, trotz allem nutzen wollen.

Dann beginnst du zu filmen und du weißt ganz genau, die Gefilmten fühlen sich wertgeschätzt, dass du sie filmst, sie fühlen sich wichtig genommen. Schon hast du sie in der Hand. Und weil du der Profi bist und die Porträtierten die Laien, kannst du sie filmen im schlechten Licht, du kannst das Zittern der Hände filmen, das Stottern beim Reden, das bleiche Gesicht: Sie merken es nicht. Und wieder im Studio, kannst du alles so schneiden, kürzen und zwischenschneiden, wie es deiner Gesinnung entspricht.

Was für ein Traumjob. Mit ihren Zwangsgebühren bezahlen dich deine Zuschauer dafür, dass du mit deinen Filmen deine Weltanschauung verbreiten darfst. Auch wenn sie deine Weltanschauung nicht mögen. Sie garantieren dir Arbeitsbedingungen, die du sonst vielleicht nirgends findest.

Donat Hofer, der SRF-Mann, hat Roman verraten, dass er für seinen Filmbericht 28 Arbeitstage bezahlt erhält. Exklusiv Spesen. Einen solchen Job gibst du nicht freiwillig her. Da trifft es sich, dass du die gleiche Weltsicht hast wie dein Arbeitgeber. Und solltest du jemals Zweifel bekommen, steckst du sie besser gleich weg.

So war es schon damals, als ich für die Tagesschau unterwegs war – so ist es noch heute, Jahrzehnte später. Donat Hofer hat es mir vorgeführt. Geändert hat sich seither wohl nur, dass seine Stelle nicht mehr so sicher ist, wie es meine war. Auch deshalb muss er so kräftig die Trommel der Propaganda rühren. Damit er auch nach dem 8. März als sympathischer Kumpel im Dienste des Mainstreams auf Reportage gehen darf.

***

Was aber lernen Menschen, die selber kritische Fragen stellen, aus der Erfahrung von Prisca, Roman und Christian? Sie lernen, dass kritisches Denken geschützt werden muss. Sie lernen, dass es sich nur entfalten und nur entdeckt werden kann, wenn es seinen eigenen Raum hat. Wenn es umgeben von Wohlwollen ist, von echtem Interesse, von Neugier, von Inspiration und von Liebe. Im Mainstream findet man diese Wertschätzung nicht.

Für ein freies Denken sind die Mainstreammedien feindliche Territorien. Sie reden es schlecht, sie verunglimpfen es, sie warnen davor, sie greifen es an, sie verschweigen es, sie bekämpfen es – sie können es nicht ertragen. Wer als freier, kritischer Mensch den Schalmeientönen des Mainstreams folgt, hat schon verloren.

Prisca, Roman und Christian versuchten es. Sie wollten die Chance nutzen, ihr Denken im Fernsehen erklären zu können. Ob es richtig war, dies zu tun, ist eine müßige Frage. Sie haben es getan, und was geschehen ist, hat seinen Sinn. Vielleicht liegt der Sinn ihrer Erfahrung darin, einer nächsten Verlockung zu widerstehen. Denn die Chance ist in Wirklichkeit eine Falle.

Deshalb: Wenn das Fernsehen kommt und dir ein Angebot macht – sag Nein! Das Fernsehen meint es nicht gut. Weil es dich nicht versteht. Weil du sein Weltbild bedrohst.

Du willst die Menschen im Mainstream erreichen? Dann bleibe auf deinem Weg. Gehe voran, bis sie dich finden.

Nicolas Lindt (*1954) war Musikjournalist, Tagesschau-Reporter und Gerichtskolumnist, bevor er in seinen Büchern wahre Geschichten zu erzählen begann. In seinem zweiten Beruf gestaltet er freie Trauungen, Taufen und Abdankungen. Der Autor lebt mit seiner Familie in Wald und in Segnas.

Der Fünf Minuten-Podcast «Mitten im Leben» von Nicolas Lindt ist zu finden auf Spotify, iTunes und Audible.

Neues Buch: «Orwells Einsamkeit - sein Leben, ‚1984‘ und mein Weg zu einem persönlichen Denken». Erhältlich im Buchhandel - zum Beispiel bei Ex Libris oder Orell Füssli

Alle weiteren Informationen: www.nicolaslindt.ch

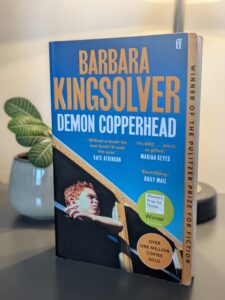

„First, I got myself born.“ Mit diesem ersten Satz macht Barbara Kingsolver in ihrem Roman „Demon Copperhead“ von Anfang an klar, dass Damon (wie der Protagonist eigentlich heißt) schon früh im Leben viel Verantwortung übernehmen muss – zu viel. Der Roman liefert Erklärungsansätze für die Wahl Donald Trumps und ist damit die klügere Alternative für jene, die – wie ich – aus ähnlichem Erkenntnisinteresse gerne zu „Hillbilly Elegy“ von J. D. Vance greifen würden, aber ungern Texte von Autoritären lesen wollen.

„First, I got myself born.“ Mit diesem ersten Satz macht Barbara Kingsolver in ihrem Roman „Demon Copperhead“ von Anfang an klar, dass Damon (wie der Protagonist eigentlich heißt) schon früh im Leben viel Verantwortung übernehmen muss – zu viel. Der Roman liefert Erklärungsansätze für die Wahl Donald Trumps und ist damit die klügere Alternative für jene, die – wie ich – aus ähnlichem Erkenntnisinteresse gerne zu „Hillbilly Elegy“ von J. D. Vance greifen würden, aber ungern Texte von Autoritären lesen wollen.