„Nur die Illusion von Schutz“

Die Risiken sozialer Medien für Kinder und Jugendliche sind bekannt: Suchtverhalten, algorithmisch verstärkte schädliche Inhalte, psychische Belastungen. Australien hat als erstes Land im Dezember 2025 eine Altersgrenze für soziale Medien eingeführt; Spanien, Frankreich und Großbritannien bringen ähnliche Regelungen auf den Weg. Diese Woche zeigte Bundeskanzler Friedrich Merz „viel Sympathie“ für die entsprechenden Vorschläge von SPD und CDU. Neben den detaillierten Regulierungsfragen, die hinter dem Verbot stehen – EU-Kompetenzen, App-Design, Durchsetzbarkeit – wirft die Debatte grundsätzliche verfassungsrechtliche Fragen auf: Wie verteilt das Grundgesetz Verantwortung zwischen Staat, Eltern und Kindern? Welche Rolle spielt Schutz – und wo beginnt Bevormundung? Darüber haben wir mit Friederike Wapler, Professorin für Rechtsphilosophie und Öffentliches Recht an der Johannes-Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, gesprochen.

1. Als die Debatte um ein Social-Media-Verbot für Kinder und Jugendliche in Deutschland aufkam – was haben Sie da gedacht?

Mein erster Gedanke war: Hier wird wieder einmal über Kinder und Jugendliche gesprochen, ohne mit ihnen zu sprechen. Ein Verbot, soziale Medien zu nutzen, greift tief in das gegenwärtige Leben von Kindern und Jugendlichen ein. Es wäre gut, wenn Parteien und Parlamente Formate fänden, um mit Kindern und Jugendlichen zu Themen ins Gespräch zu kommen, die ihre Leben unmittelbar betreffen. Darauf haben Kinder und Jugendliche ein Recht. Gerade wenn es um die sozialen Medien geht, wäre es aber auch einfach gut zu wissen, was Kinder und Jugendliche in den digitalen Räumen wirklich machen, wie sie den Gefährdungen, denen sie dort ausgesetzt sind, begegnen und wie sie selbst die Wirkung von Verboten einschätzen. Ich bin mir sicher: Wenn die Politik Kinder und Jugendliche fragt, wie soziale Medien für sie sicherer gestaltet werden können, wird sie differenzierte und konstruktive Antworten bekommen – auch dazu, wie einfach es ist, Verbote zu umgehen. Das zeigt sich gerade zum Beispiel in Australien.

2. Welche Rolle spielen die sozialen Medien für die Entwicklung von Kindern und Jugendlichen im demokratischen Rechtsstaat? Ein Großteil des Soziallebens von Jugendlichen findet auf Social Media statt. Könnte ein Verbot da nicht womöglich selbst schädlich sein?

Es ist bei Kindern und Jugendlichen nicht anders als bei Erwachsenen: Die sozialen Medien sind Fluch und Segen zugleich. Sie bieten Kontakt, Information und Unterhaltung, aber sie machen auch süchtig, konfrontieren mit verstörenden Inhalten und lenken von wichtigeren Dingen ab. Wenn wir ihre Bedeutung für den demokratischen Staat betrachten, ist es genauso ambivalent: Soziale Medien bieten Möglichkeiten der Information und Teilhabe, verbreiten aber auch Falschinformationen und können Radikalisierungen auslösen oder antreiben.

++++++++++Anzeige++++++++++++

In Good Faith: Freedom of Religion under Article 10 of the EU Charter

Jakob Gašperin Wischhoff & Till Stadtbäumer (eds.)

Freedom of religion, its interaction with anti-discrimination law, and the autonomy of churches are embedded in a complex national and European constitutional framework and remain as pertinent and contested as ever. This edited volume examines the latest significant developments and critically assesses the interpretation of freedom of religion in EU law.

Get your copy here – as always, Open Access!

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Ein Verbot ist für einige Kinder und Jugendliche und auch für deren Eltern sicherlich entlastend. Es kann aber auch negative Folgen haben. Solange ältere Jugendliche und Erwachsene soziale Medien nutzen, wird es für die Jüngeren einen Anreiz geben, sich über Verbote hinwegzusetzen. Dann werden die sozialen Medien zu etwas, was man heimlich nutzt, wovon man Erwachsenen besser nichts erzählt. Gleichzeitig gibt es für die Plattformen noch weniger Gründe, sich um den Jugendschutz zu kümmern – die jungen Leute dürften ja gar nicht dort sein. Wenn es so kommt, erzeugt ein Verbot nur die Illusion, Kinder und Jugendliche zu schützen. Tatsächlich schneidet es den einen, die sich daran halten, wertvolle Teilhabemöglichkeiten ab, und lässt die anderen, die es umgehen, allein.

3. Wie verteilt das Grundgesetz die Verantwortung für Schutz, Erziehung und Selbstbestimmung zwischen Staat, Eltern und Kindern?

Wenn ich diese Frage auf das Thema „Medien“ beziehe, dann sieht es so aus: Kinder und Jugendliche haben Freiheitsrechte. Ihre Informationsfreiheit erlaubt ihnen, sich aus allgemein zugänglichen Quellen zu informieren. Ihr Grundrecht auf die freie Entfaltung der Persönlichkeit umfasst die Nutzung von Medien zur Unterhaltung, Entspannung und Vernetzung. In der UN-Kinderrechtskonvention gewährleistet Artikel 17 Kindern und Jugendlichen ein Recht auf Zugang zu Medien. Diese Rechte sollten der Ausgangspunkt der Überlegungen sein.

Nun fällt Medienkompetenz nicht vom Himmel, sondern muss erworben werden. Kinder und Jugendliche dabei zu unterstützen und zu begleiten, ist erst einmal Aufgabe der Eltern. Eltern und Kinder haben das Recht, vom Staat unbehelligt auszuhandeln, was für sie in ihrer konkreten Lebenssituation der beste Umgang mit sozialen Medien ist. Das kann auf ein Verbot hinauslaufen, aber auch auf ganz verschiedene Formen der Begrenzung und Kontrolle.

Wenn ein Gesetz Kindern und Jugendlichen pauschal verbietet, soziale Medien zu nutzen, dann greift das nicht nur in Grundrechte der Kinder, sondern auch in das Erziehungsrecht der Eltern ein. Wie jeder Eingriff in Grundrechte muss auch so ein Verbot verfassungsrechtlich gerechtfertigt sein. Für starre Altersgrenzen, wie sie im Moment diskutiert werden, muss es besonders gute Gründe geben. Der Gesetzgeber müsste darlegen, dass Kinder und Jugendliche bis zum Alter von 14 oder 16 Jahren typischerweise nicht die notwendige Einsicht und Unterstützung haben, um verantwortlich mit sozialen Medien umzugehen. Oder er müsste nachweisen, dass die Nutzung sozialer Medien Kindern und Jugendlichen mit hoher Wahrscheinlichkeit schadet. Mit diesem Nachweis steht und fällt die Rechtfertigung eines Verbotes.

4. Halten Sie es vor diesem Hintergrund für eine gute Idee, die Verantwortung für Medienkompetenz auf den Staat zu verschieben?

Mit einem Verbot versucht der Staat, eine Gefahr abzuwehren, aber sicherlich nicht, Kindern und Jugendlichen Medienkompetenz zu vermitteln. Medienkompetenz erwirbt man, indem man Medien nutzt. Wer digitale Räume nicht betreten darf, wird nicht lernen, sich kompetent in ihnen zu bewegen.

Ich würde den Staat an dieser Stelle aber gar nicht heraushalten wollen. Man sollte Eltern und andere Erziehungsberechtigte nicht mit der Aufgabe allein lassen, Medienkompetenz zu vermitteln. Vielen Erwachsenen fällt es schwer, mit der Entwicklung im digitalen Raum mitzuhalten, und sie wissen oft nicht, wie sich Kinder untereinander beeinflussen. Hier hat der Staat andere Möglichkeiten, Medienkompetenz zu stärken. Er hat einen Bildungsauftrag in der Schule und kann außerschulische Jugendarbeit fördern.

Wichtig ist, Kindern ein Lernen über gehaltvolle Erfahrungen zu ermöglichen. Wir sperren sie ja auch nicht in den Häusern ein, weil sie auf der Straße überfahren werden könnten. Stattdessen erklären wir ihnen die Verkehrsregeln, üben das richtige Verhalten im Straßenverkehr und regeln den Autoverkehr, damit Kinder sich auch allein sicher im Straßenraum bewegen können. Im Idealfall wirken der Kompetenzerwerb im Elternhaus, die Bildungsarbeit in Kita, Schule und Jugendarbeit und der staatliche Jugendschutz zusammen.

5. Die Gefahren für Kinder und Jugendliche im digitalen Raum sind schon lange bekannt. Warum, meinen Sie, führen wir diese Debatte gerade jetzt? Und ist es ein Zufall, dass gleichzeitig auch die Forderung erhoben wird, das Strafmündigkeitsalter abzusenken?

Ich fürchte, wir erleben gerade auf vielen Ebenen ein Phänomen, das man symbolische Gesetzgebung nennt: Wenn die Politik ein komplexes Problem nicht lösen kann, demonstriert sie mit einer vermeintlich einfachen Lösung Handlungsfähigkeit. Die Ursachen des Problems werden damit aber nicht angegangen. Im Falle der sozialen Medien wäre es sinnvoller, sichere digitale Räume für Kinder und Jugendliche zu gestalten – besser noch für alle Menschen. Es kann ja niemand ernsthaft behaupten, für Erwachsene sei in den sozialen Medien alles gut. Jugendschutz und allgemein Persönlichkeitsschutz in der digitalen Welt durchzusetzen, ist aber ungleich schwieriger, als ein Verbotsgesetz zu schreiben. Was die Delinquenz von Kindern unter 14 Jahren angeht, reicht ein oberflächlicher Blick in die Fachliteratur, um zu erkennen, dass der strafrechtliche Weg nicht hilfreich ist. Besser wäre es, die Kinder- und Jugendhilfe so auszustatten, dass sie diesen Kindern helfen kann, in Zukunft nicht weiter straffällig zu werden. Das aber ist fachlich anspruchsvoll und teuer.

Wenn man die beiden Forderungen nebeneinanderlegt, erkennt man, wie hier mit Klischees von Kindheit argumentiert wird, die noch dazu einander widersprechen: Hier das unmündige Kind, das die Folgen seines Handelns nicht überblicken kann und deswegen auf Instagram seiner Lieblingsband nicht folgen darf. Dort das delinquente Kind, das gefälligst die Folgen seines Handelns tragen soll. Beide Annahmen werden der Vielfalt der Lebenswelten von Kindern und Jugendlichen nicht gerecht.

*

Editor’s Pick

von EVA MARIA BREDLER

Man macht ja vieles falsch im Leben, aber dass man falsch atmen kann, darauf bin ich vor James Nestors „Breath“ noch nicht gekommen. Bitte nehmen Sie’s mir nicht übel, aber – rein statistisch – sind auch Sie schuldig: 90 % der Bevölkerung atmen falsch und setzen sich damit einer Reihe chronischer Krankheiten aus: Asthma, ADHS, Depression, Burnout, you name it. Weil Nestor unter einigen davon litt, schickte ihn sein Arzt zu einem Atemkurs. Dort erlebte er etwas so Erstaunliches, dass er zehn Jahre lang zur Kunst des Atmens recherchierte. Das Ergebnis ist ein Buch, das nicht nur mein Leben verändert hat. Nestor ist ein präziser und humorvoller Autor, der nichts blind glaubt und alles selbst austestet: von Nasenatmen über „Tummo“ (einer Atemtechnik, die die belgisch-französische Anarchistin und Opernsängerin Alexandra David-Néel in den 1920ern nach Europa brachte) bis hin zu Techniken, die Olympioniken nutzen. Ich kam aus dem Staunen nicht raus und schämte mich zugleich, mehr über Staatsorgane als über meine eigenen zu wissen. Ich habe das Buch vielfach verschenkt, und fast alle Beschenkten schenken es weiter. Es ist ein Schneeballsystem körperlicher Aufklärung. Falls es Sie nicht bald erreicht – der Kauf lohnt sich.

*

Die Woche auf dem Verfassungsblog

zusammengefasst von EVA MARIA BREDLER

Nicht nur Jugendlichen fällt es schwer, sich der Dopaminfalle von Endlosfeeds zu entziehen, und nicht nur Jugendliche leiden unter den psychischen Folgen. Nun gibt es jedoch eine ganz neue Kategorie schädlicher Inhalte: Seit Musk das KI-Tool Grok auf X integrierte, wurden massenhaft sexualisierte Deepfakes von realen Frauen und Minderjährigen generiert und verbreitet. Wie verteilt hier das (Straf)recht die Verantwortung – und wie sollte sie verteilt werden? SUSANNE BECK und MAXIMILIAN NUSSBAUM (DE) haben Antworten.

++++++++++Anzeige++++++++++++

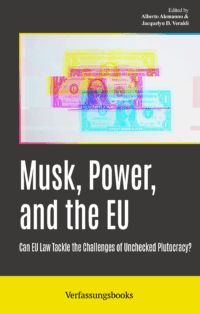

Musk, Power, and the EU: Can EU Law Tackle the Challenges of Unchecked Plutocracy?

Alberto Alemanno & Jacquelyn D. Veraldi (eds.)

“In a viable, participatory democracy, no person, corporation or interest group – no matter how loud, wealthy, or powerful – stands above the law. This collection of important research explores vital, vexing questions of how to defend the rule of law in the European Union against a frontal challenge by oligarchic forces claiming to act in the interest of Western ideals. It is an uncomfortable debate but one that the authors confront with intellectual vigor and admirable European self-awareness.”

– David M. Herszenhorn, Editor at The Washington Post

Get your copy here – as always, Open Access!

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Auch Karlsruhe hat letzte Woche Verantwortung kartiert, allerdings in anderem Kontext: Das Bundesverfassungsgericht hat eine Verfassungsbeschwerde nicht zur Entscheidung angenommen, die ein im Gazastreifen lebender Palästinenser gegen Genehmigungen für die Ausfuhr von Kriegsgerät nach Israel erhoben hatte. Der ausführliche Nichtannahmebeschluss erschien pünktlich zur Münchner Sicherheitskonferenz und war für FLORIAN MEINEL (DE) Anlass, über Pseudogrundrechtsschutz und das Verfassungsrecht des hybriden Krieges nachzudenken.

Um Palästina ging es auch vor dem englischen High Court. Nachdem das Innenministerium „Palestine Action“ verboten hatte, hob das Gericht das Verbot nun wieder auf – zum Erstaunen vieler, denn in Sachen nationale Sicherheit sind die britischen Gerichte traditionell zurückhaltend. ALAN GREENE (EN) analysiert die Gefahren weitreichender exekutiver Ermessensspielräume und die Bedeutung des Urteils für die rechtliche Terrorismusbekämpfung.

Viel Beachtung fanden auch die mündlichen Verhandlungen des Internationalen Gerichtshofs in The Gambia v Myanmar, die am 29. Januar zu Ende gingen. Im Mittelpunkt stand der Genozidvorsatz. Doch was folgt eigentlich aus einem Genozid-Urteil? Für KHAN KHALID ADNAN (EN) ist das die schwierigste Frage, und sie führt ihn (und uns) in das Recht der Rechtsfolgen.

Die USA akzeptieren schon seit inzwischen 40 Jahren nicht mehr die obligatorische Gerichtsbarkeit des IGH. Und nun wollen sie sich auch sonst vom UN-System verabschieden: Am Rande des Weltwirtschaftsforums in Davos hat Trump nun das „Board of Peace“ gegründet – als Gegenentwurf zu den UN. In Europa überwog Skepsis, Merz verwies auf verfassungsrechtliche Bedenken. VALENTIN VON STOSCH (DE) zeigt: An diesen Bedenken ist durchaus etwas dran.

Vielleicht können die USA auch komplett auf Friedensorganisationen verzichten. Immerhin verkündete Trump (nur Tage vor Maduros Entführung): „We’re protected by a thing called the Atlantic Ocean.“ Darin deutet sich schon die Kernidee der neuen nationalen Sicherheitsstrategie der USA an, die auf hemisphärische Dominanz setzt. CARL LANDAUER (EN) erklärt, wie sie alte Einflusssphären reaktiviert und sich an einer projizierten „westlichen Zivilisation“ abarbeitet.

Ganz so sicher scheint sich Trump seiner Sache doch nicht zu sein. Vor den anstehenden Midterms drängt Trump nun auf eine „Nationalisierung“ der US-Wahlen – ohne jede verfassungsrechtliche Grundlage. JOSHUA SELLERS (EN) warnt, dass Trumps Idee dazu beitragen könnte, das öffentliche Vertrauen weiter zu erodieren und die Desinformation über die Integrität des Wahlprozesses zu steigern.

Auch Deutschland diskutiert wieder die Integrität der Wahl: Die Paritätsdebatte ist zurück. Während sie politisch in Gang kommt, ist sie rechtswissenschaftlich in einer Sackgasse gelandet. FABIAN MICHL (DE) erklärt, warum eine historische Perspektive weiterhilft.

Ebenfalls historisch: Im Dezember einigten sich die EU und vier Mercosur-Staaten – nach 25 Jahren Verhandlungen! – auf das EU–Mercosur-Abkommen. Nun hat eine knappe Mehrheit im Europäischen Parlament den EuGH um Prüfung gebeten, ob das Abkommen mit Unionsrecht vereinbar ist. Für GESA KÜBEK (EN) hat sich das Parlament damit ins eigene Knie geschossen und Mitspracherechte verspielt.

Mitspracherechte verdient haben sich dagegen Personen, die sich zwischen den Geschlechtern identifizieren, aber keine somatische Intergeschlechtlichkeit aufweisen. Der österreichische Verfassungsgerichtshof hat ihnen nun einen eigenen Geschlechtseintrag – wie inter und divers – oder dessen Streichung zuerkannt. ELISABETH HOLZLEITHNER (DE) bespricht diese freundliche Entscheidung inmitten einer eher unfreundlichen Debatte.

Währenddessen hat Generalanwältin Ćapeta in ihren Schlussanträgen vorgeschlagen, den Beschluss der Kommission für nichtig zu erklären, mit dem diese die zuvor gestoppten Geldzahlungen an Ungarn wieder freigeben wollte. Rechtsstaatlichkeit könne bei systemischen Defiziten nicht am Gesetzestext allein gemessen werden. Für TÍMEA DRINÓCZI (EN) bietet dieser Ansatz Orientierung für den verfassungsrechtlichen Wiederaufbau nach illiberalen Regimen.

Um es gar nicht erst so weit kommen zu lassen, sollen – nach dem Vorbild des BVerfG im vorletzten Jahr – nun auch Landesverfassungsgerichte resilienter gemacht werden. CHRISTIAN WALTER und SIMON FETSCHER (DE) bewerten, wie gut das dem aktuellen Entwurf der Berliner Justizsenatorin gelungen ist.

Und schließlich analysieren ANNA LUMERDING und MELANIE MAURER (EN) die Klimabeschwerde mit dem schönen Namen Fliegenschnee u.a. v. Österreich, die der EGMR für unzulässig erklärte.

Außerdem ging unser Symposium „Reflexive Globalisation and the Law“ (EN) zu Ende. PEER ZUMBANSEN sieht Katastrophenrecht als Methode und Jurist*innen in der Verantwortung, offenzulegen, wie das Recht zur Normalisierung dieser anhaltenden Gewalt beiträgt. JULIA ECKERT schließt das Symposium mit der Frage, wozu die Reflexion kolonialer Kontinuitäten im Recht eigentlich dient.

Vielen Dank, dass Sie trotz dopamindominierter Aufmerksamkeitsspanne bis hierhin gelesen haben. Wir versuchen weiterhin, schädliche Inhalte zu reduzieren (die Weltlage macht es uns nicht leicht). Aber so ein Endlos-Feed ist eigentlich gar keine schlechte Idee.

*

Das war’s für diese Woche.

Ihnen alles Gute!

Ihr

Verfassungsblog-Team

Wenn Sie das wöchentliche Editorial als E-Mail zugesandt bekommen wollen, können Sie es hier bestellen.

The post „Nur die Illusion von Schutz“ appeared first on Verfassungsblog.